Please scroll down for English

מזל וברכה נפתחה בצהרי שישי בסוף יולי, כשעה אחרי שתי אזעקות באזור תל-אביב, קונטקסט בהחלט דרמטי לתערוכה שעניינה ההשפעה של ייצוגי אמונות טפלות ומתיסוים באמנות ישראלית עכשווית. על התערוכה אפשר לחשוב באופן נרחב יותר כהתבוננות בפיצול, החלקי בלבד, שחל בין אמונה לאמנות מאז היו כמעט אחד בחברות אנושיות מוקדמות או ראשוניות. האמנות,מבחינה אנתרופולוגית, צמחה כחלק מטקסים רליגיוזים.כיום היא דיספלינה נפרדת אך יש בה היבטים רוחניים,חיפוש רוחני (גם כיום כשהגוון הצרכני מקבל משקל יתר).

מזל וברכה מוצגת בקומה השניה בבית התפוצות בחלל ששמו שער האמונה ובעבר הוצגו בו דגמי בתי כנסת. משתתפים בה ארבע עשר אמנים ואיכות העבודות מגוונת. בין הבולטות לטובה העבודות של אבי סבח ואסי משולם,רפעת חטאב, נורית ירדן וגרי גולדשטיין. לצד האמנות העכשווית גם מוצג הקבץ יפה מאוסף היודאיקה המצוין של ויליאם גרוס.

העבודה של רווית מישלי מרתקת ויוצאת דופן ביחס שהיא מכוננת בין תולדות האמנות היהודית לאמנות העכשווית. הקישור שלה לנושא התערוכה בכללותו עקיף, אך היות ומדובר בעבודה מבריקה היבט זה הוא חסר חשיבות.

מישלי יצרה את עבודתה,ללא כותרת, בתוך הדגם המוקטן של בית הכנסת בדורא ארופוס, אתר שהחשיבות הארכיאולוגית שלו רבה וחשיבותו לפרשנות אמנות יהודית עצומה. ההכרה המועטה יחסית של גוף היצירה הזה בארץ מעידה על הקושי בחשיבה על יחסי אמנות יהודית ישראלית באופן שאינו דוגמטי. ההצבה שמישלי בחרה בה מהותית לעבודה מעבר לשיקולים אסטטים.

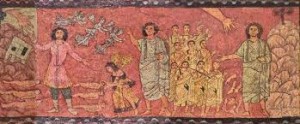

בית הכנסת התגלה בחפירות ארכיאולוגיות בסוריה,בשרידי העיר דורא ארופוס ב 1932. הוא מכיל עשרות ציורים פיגורטיביים המתארים סיפורים מהתנ”ך בהם סיפור עקדת יצחק, משה מקבל את לוחות הברית ומוציא את בני ישראל ממצרים,סצנות ממגילת אסתר וגם חלקים מחזון יחזקאל. בית הכנסת תוארך ל 244 לספירה לפי כתובת ארמית שהשתמרה בו. השתמרות בית הכנסת נובעת, כנראה, מכך שבעת המלחמה בין הרומים לפרסים (שלבסוף כבשו והחריבו את העיר) נפסק השימוש בו והוא מולא בעפר כחלק מביצורי העיר. כך הוא הפך לדוגמא נדירה ביותר של ציורי קיר יהודיים מתקופה זו והוא מאתגר את התפיסות הדוגמטיות בעניין ההשפעה של הציווי של הדיבר הראשון. הפרסום המדעי הראשון לגביו ראה אור ממש ערב מלחמת העולם השנייה, ב 1939 וחלקי בית הכנסת המקוריים נשמרו במוזיאון הסורי הלאומי בדמשק.

מישלי מתבלטת כבר כמה שנים במיצבים מרשימים (הפי ניישן שהוצג בתערוכת בוגרי התואר השני בבצלאל ב 2010, ווריאציה שלה הוצגה בביאנלה בהרצליה) ועבודות קטנות יותר כמו סידרת רבידים עם מוטיבים של ישראלינה של שנות ה 50 וה 60. ההצבה במזל וברכה היא כאמור בתוך דגם הקיר המערבי של בית הכנסת בדורא ארופוס, (שחזור קנה מידה 2:1 )יצרה. היא רחבה קטנה של חול ובה דמויות סכמטיות עשויות פולאוריטן ומצופות חול או עפר שנראה כטפטופי בוץ. אלו הן מריונטות, חוטיהן גלויים והצופים יכולים להקימן לתחייה ולשמוט אותן כרצונם. מערך המריונטות ופרטים כמו ידיים אוחזות גולגולת או ספק מסכה ספק גוף בתוך מקום ארון הקודש יוצרים תחושה שהן גילמו טקס כלשהו, שיש לו פוטנציאל לחזור שוב ושוב.

הקשר לחזון העצמות, שהוא הנושא המצויר הגדול ביותר בבית הכנסת, ברור בשל עיצוב המריונטות והדגשת היותן מעפר. אם מתאמצים למצוא צד אופטימי בעבודה הקודרת אפשר לחשוב על המריונטות בהקשר לסוף החזון : בְּפִתְחִי אֶת-קִבְרוֹתֵיכֶם, וּבְהַעֲלוֹתִי אֶתְכֶם מִקִּבְרוֹתֵיכֶם–עַמִּי. וְנָתַתִּי רוּחִי בָכֶם וִחְיִיתֶם, וְהִנַּחְתִּי אֶתְכֶם עַל-אַדְמַתְכֶם; וִידַעְתֶּם כִּי-אֲנִי יְהוָה, דִּבַּרְתִּי וְעָשִׂיתִי–נְאֻם-ה` (יחזקאל ל”ז 14-10)

בשורת עבודות מהשנים האחרונות טיפלה מישלי בגוף באופן המגחיך אותו, מצמצם את איבריו לכדי שלד ומעלים סימני זיהוי. הכוונה לדימויים גרוטסקיים כמו פוף,2009, ניילון בצורה של כורסת פוף שמולאה בפופקורן ועליו שלד עשוי מפופקורן מודבק או התערוכה המרכז להרחקת יונים, הפחות מוצלחת, בגלריה טבי בה יצרה מישלי,מבצק, שורת דמויות דומות מאד לאלו שמוצגות במזל וברכה.

במגרש החול שיצרה מישלי בדגם דורא ארופוס הבובות במשמעות שלא היתה להם בעבר. הקישור הרעיוני לחזון יחזקאל, והחזותי לדימויי איברי הגוף הקטועים (המחרידים) ששימשו אמן במאה השלישית לספירה מצוינים.

הדימוי של המוות כשלד מרקד,מוטיב ה Danse Macabre מתקשר לאמנות נוצרית של ימי הביניים המאוחרים וגם לגלגולים העכשוויים של הדימוי בעבודות של כריסטיאן בולטנסקי (שזיקה לעבודתו ניכרה גם בעבודות של מירב סבירסקי שהציגה לא מזמן בקו 16 ). המריונטות של מישלי, שנראות כגלי עצמות שהתאבנו ומתמלאות חיים,בעזרת הצופים, יוצרות באופן סימבולי תאטרון שכחוצה זמנים ומצבי חיים בחצר בית כנסת שחרב ושב והתגלה.

אוצרת: כרמית בלומנזון

בית התפוצות, אוניברסיטת תל אביב (שער 1).

הרשמה לניוזלטר הפירסומי השבועי של “החלון” בנושאי אמנות, אירועים ותערוכות חדשות – www.smadarsheffi.com/?p=925

(הרישום נפרד מהרישום לבלוג )

נפתחה ההרשמה לקבוצת סיורי האמנות 2014-2015 מידע בעמודת הרצאות וסיורים

Ravit Mishli’s installation in the exhibition Mazal U’Bracha: Myths and superstitions in contemporary Israeli art

The opening of the exhibition Mazal U’Bracha took place at the Beit Hatfutsot-Museum of the Jewish People on a Friday afternoon in late July, about one hour following two red alerts – definitely a dramatic context for an exhibition on the impact of the representations of myths and superstitions in contemporary Israeli art. In a broader sense, the exhibition may be seen as contemplating the partial split between emunah and omanut- two words spelled almost the same in Hebrew, meaning faith and art, two words which used to comprise a single entity in early human society. From an anthropological aspect, art was partly an outgrowth of religious ceremonies; it is currently a separate discipline yet still retains aspects of a spiritual search (even now, when the commercial aspect has considerable weight).

Mazal U’Bracha is installed in the Museum’s “Gate of Faith” area, formerly the space for exhibiting models of old synagogues. There are 14 artists participating in the exhibition, with varying quality of works. Outstanding are works by Avi Sabah, Raafat Hatab, Nurit Yarden and Gary Goldstein. The William Gross Judaica Collection is also on exhibit along with the contemporary art.

Ravit Mishli’s installation fascinates with the unusual relationship it establishes between the history of Jewish art and contemporary Israeli art. The brilliance of the work makes it unimportant that it is not explicitly linked to the them of the exhibition.

Mishli created the untitled work inside the miniature model of the Dura Europos synagogue (244 CE). The original site was of great archaeological importance, and tremendously vital to the interpretation of Jewish art. The relatively low level of familiarity among Israelis with the Dura Europos art demonstrates the difficulty in thinking about the relationship between Jewish and Israeli art in a non-dogmatic way. Mishli’s choice of installation is essential to the work, beyond its aesthetic considerations.The synagogue was discovered in 1932 during excavations in Syria among the ruins of the city. It contains dozens of figurative paintings describing Bible stories, such as the Binding of Isaac, Moses receiving the Tablets of the Law, and taking the Israelites out of Egypt, scenes from the Scroll of Esther and portions of Ezekiel’s Vision of the Dry Bones. Dating was according to a well-preserved Aramaic inscription; the walls survived because during the war between the Romans and Persians (who finally destroyed the city) it was filled with earth as fortifications. The wall paintings became the rarest example of Jewish art of the 3rd century, challenging the accepted explanation of the Second Commandment not to make “graven images.” The first scholarly article on the finds was published on the eve of World War II in 1939, and the original sections of the synagogue were stored in the National Museum of Syria, Damascus.

Mishli has been noticeable for her impressive installations over recent years, such as “Happy Nation” shown in the Bezalel MFA exhibition in 2010, with a variation exhibited in the Biennale at the Herzliya Museum of Contemporary Art, and smaller works such as her “Revidim” series with its motifs of Israeliana of the 50s and 60s.

The installation is placed inside the western section of the half-size scaled model of the Dura Europos Synagogue. Mishli created a small square of sand with schematic figures made of polyurethane covered with sand or dirt which looks like dripped mud. These are marionettes with visible strings which visitors were able to pull up, thus “resuscitating” the figures, or allowing them to drop down.(The strings were very soon pulled so harshly the “interactive” aspect of the exhibition was cancelled). The array of figures, with various details such as hands holding skulls or perhaps masks, clumps looking like bodies inside the Holy Ark, create a feeling that they are embodying a sacred text with the potential of being repeated ad infinitum.

There is a clear association to Ezekiel’s Vision of the Dry Bones, which is the largest painting in the synagogue, due to the design of the marionettes and the emphasis on their being made from dust. If we seek the optimistic side of this dark work, we can think of the marionettes in the context of the end of the Vision: “You shall know, O my people, that I am the LORD, when I have opened your graves and lifted you out of your graves. I will put My breath into you and you shall live again, and I will set you upon your own soil. Then you shall know that I the LORD have spoken and have acted- declares the LORD.”(Ezekiel 37:10-14).

In her series of works over recent years, Mishli addressed the body but ridiculed it, minimizing the limbs to make it into a skeleton and concealing any identifying signs. The intention to make grotesque images, such as in her piece Pouf (2009), which featured a plastic armchair stuffed with popcorn onto which a skeleton of popcorn was pasted, or her less successful Center for Exterminating Pigeons in the Tavi Gallery, Tel Aviv, with rows of figures similar to the ones in MazalU’Bracha, but made of dough.

Placed in the field of sand which Mishli created inside the model of the Dura Europos Synagogue, the marionettes take on a meaning that they lacked in the past. The associative philosophical and visual link to the (horrific) images of severed limbs, which served a 3rd century artist,are excellent.

The motif of the danse macabre, Death as a dancing skeleton, is associated with Late Medieval Christian art as well as with contemporary transformations of the image bu artists such as Christian Boltanski (whose impact is recognizable in works by MeravSvirsky recently shown at Kav 16). Mishli’s marionettes, looking like heaps of fossilized bones which have life breathed into them with the help of viewers (before the strings became tangled and ruined) symbolically create a timeless theatre and life situations in the ruins of a rediscovered synagogue courtyard.

Curator: Carmit Blumensohn

Beit Hatfutsot-Museum of the Jewish People, Tel Aviv University (Gate 1).

Join the mailing list for Window’s weekly informational advertising newsletter on art, special events, and openings: www.smadarsheffi.com/?p=925