“עונג שבת” היה יוזמה של חיים נחמן ביאליק ליציקת תכנים רוחניים בשבת החילונית. במענה לחיפוש אחר אופי מתאים, פלורליסטי, נוסדו מפגשים ציבוריים עם אנשי רוח, שנערכו מדי שבת בתל אביב, ובהם הרצאות ודיונים בקשת רחבה של תחומי דעת, מתנ”ך, היסטוריה, ופילוסופיה ועד גאוגרפיה ובוטניקה. מפגשים ראשונים נערכו ב 1927 והמשיכו להתקיים עשרות שנים לאחר מותו של ביאליק. תחילה היו ההתכנסויות בבתים פרטים ותוך שנתיים הפכו כה פופולריים שעם חניכת אולם “אוהל שם” ב 1929 הפך האולם, שבו 1,200 מושבים, למשכנו הקבוע של מפעל “עונג שבת”.

ביאליק, באמצעות מפגשי עונג שבת, תרם משמעותית ליצירת סטטוס קוו של קיום אירועי תרבות בשבת וחגים והפיכת התרבות למרכיב חשוב בדיוקן העיר, לא פחות מכלכלה ומסחר. למרות שביאליק לא שמר שבת, במובן האורתודוקסי, חשש מכך שאין “שום מלט רוחני” המאחד את תל אביב ” לחטיבה שלמה בעלת תרבות אחת”. המפגשים ששילבו הרצאות, שירת מקהלה וקהל וטקס הבדלה, הציעו פורמט תרבותי חדש ומכיל לעיר הצעירה.

Graphite and paint on paper

לאור הצלחת המפגשים בתל אביב נוסדו מפגשים דומים ברחבי ארץ ישראל וגם בקהילות יהודיות בתפוצות.

“עונג שבת” היה גם שם ארגון מחתרתי של היסטוריונים ואנשי רוח שהקים ד”ר עמנואל רינגלבלום בגטו ורשה (והוא שנתן לו את שמו). האירגון שם לו למטרה לכתוב את היסטוריית הגטו, ויהדות פולין, מנוקדת הראות היהודית וכך לא להותיר את ההיסטוריה לנרטיב הגרמנים המרצחים בלבד. הארכיון שנכתב ונאסף תוך סיכון חיי כל המעורבים, הקיף מחקרים ועבודות על כל היבטי החיים בגטו והוטמן בקופסאות מתכת ובכדי חלב. יוזמיו ומשתתפיו של מפעל גבורת רוח זו נרצחו כמעט כולם.

בספרת התרבות היהודית-הישראלית הזיקה בין הדברים היא מעבר לזו האסוציאטיבית שיוצר השם. פרויקט עונג שבת החברתי תרבותי של ביאליק החל תריסר שנים לפני פרוץ מלחמת העולם השנייה. למרות ההבדל המהותי, הגבורה העילאית שנדרשה לאנשי אירגון “עונג שבת” בגטו ורשה, הרי שהמחויבות לחיי רוח, כערך מרכזי מקשרת בין הדברים. לכך יש להוסיף את המעמד המיוחד שהיה ליצירת ביאליק בחיים התרבותיים בגטאות – הכוונה לשירי הארץ אך גם לתיאוריו של אירועי זוועה ובמיוחד פרעות קישינב ב 1903.

המיצב של טלי נבון יוצר סביבה להרהור והתבוננות ביצירה ובריק, בתרבות הממשיכה להיווצר ובמה שנמחה. את החלל בקומה השנייה היא הופכת לחדר הסבה ליחיד/יחידה ובו כורסה ושולחן.

ספונים בחלל מבקרות/ים צופים, בעבודת הווידיאו “חלל עבודה” . ציור חללי כתיבה, בהם ציור מהתבוננות בחדר עבודתו של ביאליק, לצד חללים מדומיינים, מתחלפים ונמסים זה לתוך זה. הכתיבה נתפסת כפעולה של הגדרה עצמית ורפלקציה רוחנית, לעיתים כאקט התנגדות. בתוך כל חלל מצויר הנראה בסרט, נפער פתח בו סרט שצולם בתוך בית ביאליק, כמו שכבה נסתרת ופועמת כמו סוד, אולי מחוז חפץ ותקווה. הדימויים המוסרטים בבית יוצרים קישור, חיבור בין המדומיין והממשי, ובין זמנים, זמן הציור המופקע מהזמן הלינארי והזמן של הווה-עבר.

הצילום נאסר במפגשים כמחווה לשמירת שבת אורתודוקסית (בעוד כתיבה הייתה מותרת). בציור “הרגע שלא צולם” נבון מנכיחה את אהל שם והקהל באולם כקולאז’ המבוסס על דימויים ממקורות שונים. היא מצרפת דוברים כמו יוסף אריכא, יעקב פיכמן, דויד שמעונוביץ (לימים דוד שמעוני), עם מקהלת אהל שם וקהל שצולם מחוץ לאולם.

בין הקרנת הווידיאו לקיר הניצב לו ,ועליו הציור “הרגע שלא צולם”, מתוחים חוטים–קורים כמו נימי דם בין הפרטי לציבורי, בין חדר עבודה, עריסה אידאלית ליצירה כתובה (“חדר משלך” של ורג’יניה וולף מהדהד) לבין זירה פומבית לחשיבה ולימוד.

על קיר נוסף נבון יצרה מעין ספריה ובה צילומי מסמכים בהם מכתבים, מאמרים, רשימות על “עונג השבת” בתל אביב ועל ארכיון “עונג שבת” מגטו ורשה.

ליד הכורסה, על השולחן, מונחת מחברת ובה דיוקנאות מצוירים של אנשים שהשתתפו במפגשים בתל אביב ושהיו חלק מחברי ארגון “עונג שבת” בגטו ורשה. בין האישים המוכרים טשרניחובסקי, אשר ברש, ויעקב פיכמן בתל אביב, ומגטו ורשה ד”ר עמנואל רינגלבלום וגלה (געלע) סקשטיין ציירת שהדיוקנאות שציירה בגטו ונמצאו בארכיון עונג שבת מהווים הנצחה צוואה חזותית. המחברת מאפשרת קשר אינטימי וקרוב בין המצוירים לבין המתבוננות/ים שחוצה מקומות וזמן.

נבון מתמקדת בעונג שביצירה והתנסות בתרבות, ובמעמד הכפול שלה כאלטרנטיבה וכמעצבת מציאות, גם בתנאים וזמנים אפלים.

ד”ר סמדר שפי

אנתולוגיה-עונג שבת I טלי נבון

בית ביאליק. הקומה השנייה. בית מניה.

דר’ סמדר שפי – אוצרת התערוכה

איילת ביתן שלונסקי – אוצרת ראשית ומנהלת מתחם ביאליק

*”עונג שבת”, תערוכתה של טלי נבון היא הרביעית הנערכת במסגרת – סדרת התערוכות המחקריות “אמנות בקומה השנייה. בית ביאליק”. במסגרת זו אמניות ואמנים מפתחים עבודות לתערוכה באצירתה של ד”ר סמדר שפי תוך עבודת חקר בארכיון בית ביאליק בהנחיה צמודה של מנהל הארכיון מר שמאול אבנרי ואשת הארכיון יהודית דנון. התערוכות מאירות זוויות ספציפיות במורשת ביאליק.

לקביעת סיורים פרטיים אן הצטרפות לסיורים

שילחו Whats app ל 0507431106

עקבו אחרי באינסטגרם smadarsheffi

Tali Navon | “Oneg Shabbat” Anthology

“Oneg Shabbat,” (lit., “joy of the Sabbath”) was a project initiated by Haim Nahman Bialik to add cultural substance to the Sabbath day. Searching for content that would be suitable for the diverse population of Tel Aviv, gatherings were established with leading intellectuals that took place every Saturday in Tel Aviv. The lectures and discussions ranged over diverse fields of knowledge, from the Bible, history, philosophy, and geography to botany. The first gatherings began in 1927 and the initiative continued for decades after Bialik’s passing. After a short period, the gatherings became so popular they were assembled in Ohel Shem, the largest hall in Tel Aviv at the time. It became the permanent venue in 1929.

Oil on paper

Bialik thus made a significant contribution to establishing a status quo by holding cultural events on the Sabbath and Jewish holidays, making culture a major component in the city’s profile, no less important than its commercial aspects. Despite Bialik not observing the Sabbath observance according to Orthodox tradition, he harbored a concerned that “there was no spiritual cement” that would turn Tel Aviv “into a whole unit with a single culture.” The sessions, which integrated lectures, choral and community singing and the Saturday evening Havdalah ceremony marking the end of the Sabbath, offered a new and inclusive format for the young city.

Following the success of the Tel Aviv Oneg Shabbat, similar programs were established throughout the country as well as well as in Jewish communities in the Diaspora.

Oneg Shabbat, in Yiddish Oyneg Shabbes (Polish: Ojneg-Szabes), was also the name of an underground group of historians and intellectuals founded by Dr. Emanuel Ringelblum in the Warsaw Ghetto. Their goal was to write the history of the ghetto and Polish Jewry during World War II from their viewpoint so as not to allow the German perpetrators to determine the narrative. The Archive they collected at the risk of their lives comprised research studies on all facets of ghetto life. These were concealed in metal boxes and milk cans, then buried. Nearly all of the Archive’s initiators and participants were murdered.

In the Jewish Israeli narrative, the link between the two enterprises goes far beyond their names. Bialik’s sociocultual Oneg Shabbat project began a dozen years prior to World War II. Despite the fundamental difference, the uncompromising courage demonstrated by the Oyneg Shabes members in the Warsaw Ghetto, the link between the two projects is the deep commitment to a spiritual life as a major value. Worth mentioning is the important, is the unique place of Bialik’s oeuvre in the ghettos – poems about Eretz Israel as well as his descriptions of historical horrific events, especially the Kishinev pogroms of 1903.

Tali Navon’s installation creates an ambience for contemplation and observation of creativity and the void, a gaze at culture in formation and erasure. The space on the second floor becomes a private chamber – a sitting room furnished with an armchair and table.

From inside the space, visitors can view the video Workspace (2019) which portrays paintings of writing spaces, including Bialik’s study, merging with imaginary spaces. Writing is perceived as an act of self-determination and spiritual reflection, sometimes as an act of resistance. Within each painted space in the film is an opening through which one can see a clip filmed from inside the Bialik House, acting as a hidden layer beating like a secret heart, perhaps a realm of desire and hope. These images filmed in the Bialik House create a link between the imagined and the concrete, connecting eras, extracting the images out of our timeline, in a transition from present to past.

Photography was forbidden at the Oneg Shabbat meetings, deferring to Orthodox observance (although writing was permitted). In the painting The moment not photographed (2019), Navon makes present the Ohel Shem auditorium and its audience as a collage based on figures from various sources. She combines images of writers such as Yosef Aricha, Yakov Fichman, and David Shimonovitch (Shimoni) with the Ohel Shem choir and the audience photographed outside of the hall.

Between the video screening and the painting, web-like strings stretch like a network of veins between private and public spheres, between the ideal cradle of poetic writings and the final output, between the intimate workplace (resonating with Virginia Woolf’s “room of her own”) and the public arena of thought and study.

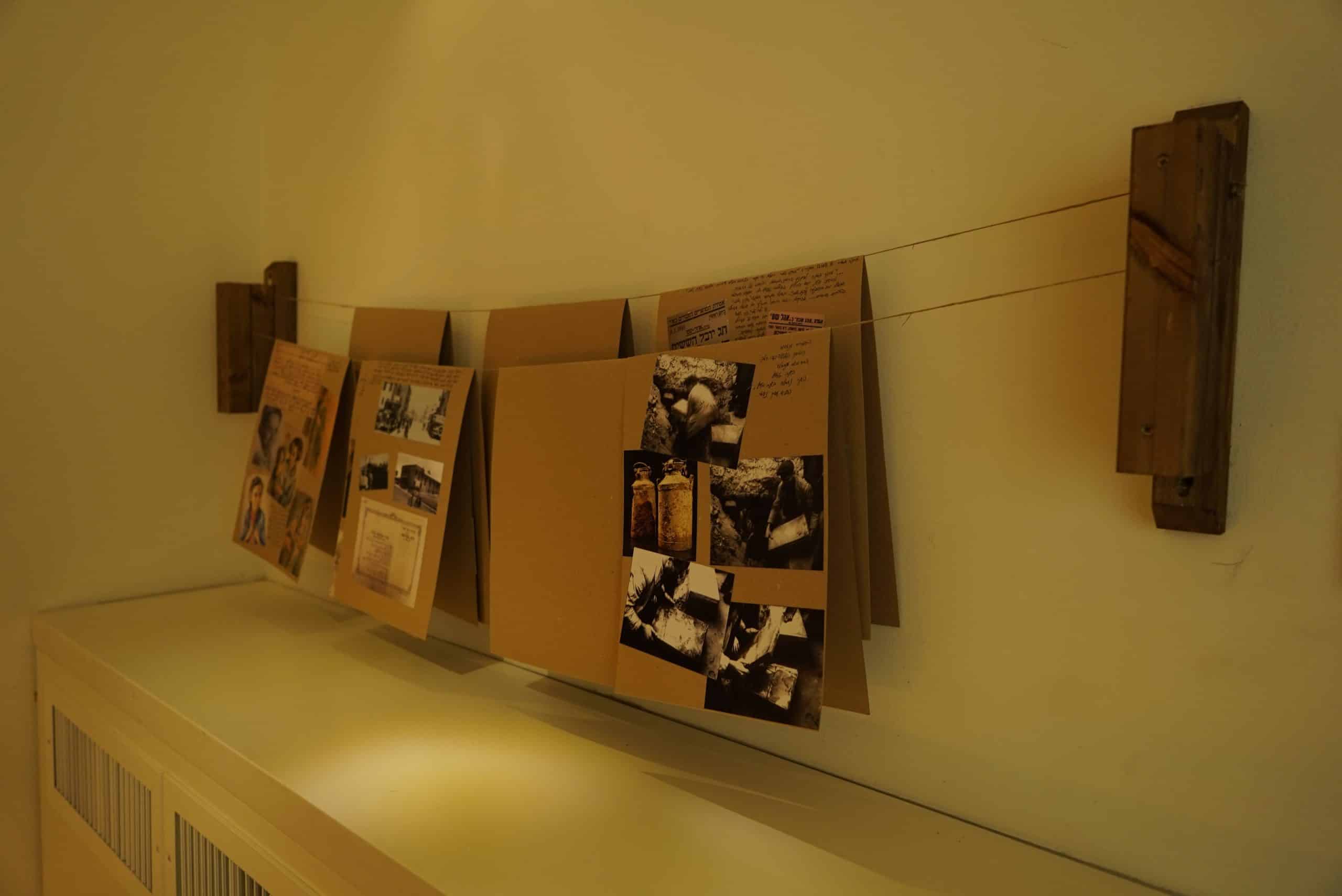

On another wall Navon built a library comprised of photocopies of letters, articles on the Tel Aviv Oneg Shabbat afternoons and on the Oyneg Shabbes Archive of the Warsaw Ghetto.

Near the armchair, on the table lies a notebook containing portrait paintings of the participants in both projects in Tel Aviv and in Warsaw. Among the more familiar names are Tchernichowsky, Asher Barash and Yakov Fichman in Tel Aviv, and from the Warsaw Ghetto, Dr. Emanuel Ringelblum and the artist Gela Seksztajn (Gele Seckstein). The latter’s portrait paintings made in the ghetto were found in the Oneg Shabbat Archives located after the war, a visual commemoration and last testament. The notebook facilitates a close connection between the depicted and the visitors perusing the pages, transcending time and place.

Navon focuses on the power of the pleasure in creation and cultural experience and its dual status as a vehicle to establish an alternative reality, even under dire conditions in dark times.

Dr. Smadar Sheffi

Bialik House Museum. The Second Floor. Beit Manya.

Dr. Smadar Sheffi – Exhibition Curator

Ayelet Bitan Shlonsky – Chief Curator and Director of the Bialik Complex

*Tali Navon’s exhibition marks the fourth in the research-based art exhibitions on the Second Floor of the Bialik House Museum. Artists develop works curated by Dr. Smadar Sheffi based on archival research in the Bialik House Archives guided by Archive Director Shmuel Avneri and Yehudit Danon to illuminate specific aspects of Bialik’s legacy.

For information about boutique Art tours in Israel please write ssheffi@gmail.com

or send a whats app message to +972-50- 7431106

Oil on paper