For English click here

“מה שהיה ומה יהיה” היא תערוכה מצוינת, אחת הטובות, ואולי הטובה ביותר של גבע הזכורה לי. היא ישירה, כנה, והקשריה הם הרבה מעבר לצימוד הקבוע של גבע ותולדות הציונות, גבע והאתוס הקיבוצי או תחושת הטפה ומידה של אלגיה שדבקה בעבודתו, וקריאת עבודתו, בשנים האחרונות ובוודאי בזו החולפת.

מדובר למעשה בשני חלקים המוצגים במקביל בשני חללים בבית ליבלינג, מהלך אוצרותי נבון של האוצרת סברינה צגלה, בוודאי לגבי אמן ותיק ובעל גוף עבודות גדול כל כך כמו גבע.

בחדר הפרויקטים בקומת הקרקע, נפרשת הצעתו של גבע לביאנלה ב-2003 – שלא התקבלה,וזו מהווה מעין תת מודע לתערוכה המרכזית המוצגת בדירת הרזידנסי בקומה השלישית. נושא העל של שני החלקים הם מעגלי הרס ובניה, כליה והתחדשות.

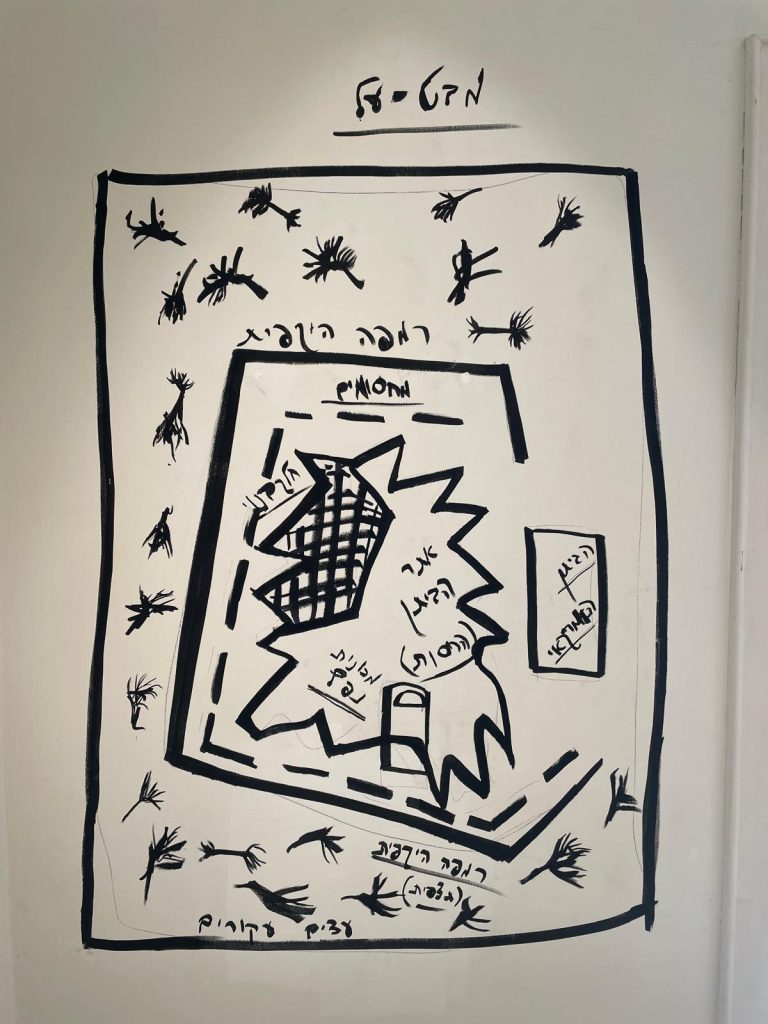

ההצעה של גבע ב 2003 הייתה להריסת הביתן הישראלי באמצעות הכנסת מכונית נפץ שתביא לקריסת הבניין, התאבדות סימבולית של הישראליות. בלתי אפשרי להימנע ממחשבה על פיגועים היסטוריים כמו פיצוץ מלון המלך דוד ב 1946 על ידי האצ”ל או אסון צור הראשון נגד מפקדת צה”ל בלבנון ב 1982. גבע הציע לנצל שיפוץ שהיה צפוי אז בבניין כדי ליצור הרס טוטלי של המבנה ולדבר על בנייתו מחדש, בין השאר בהקשרים מיתיים כמו המבול.

דומה שההצעה הוגשה בידיעה שלא תתקבל, בוודאי לא בתקופה הסוערת של ימי האינתיפאדה השנייה בהם פיגועי התאבדות רדפו זה את זה. קונצפטואלית גבע המשיך ברעיון הפיצוץ מסורת מודרנית של אמנים שמחיקה והרס היוו עבורם יצירה. בין הדוגמאות המוכרות ביותר ” Erased De Kooning Drawing” של רוברט ראשנברג מ 1953 – עבודה שבה מחק פיזית רישום של דה קוניג והעבודה Dropping of a Han vase של אי וייוי מ 1995 בה ניפץ כלי חרס סיני רב ערך כספי וסימבולי.

מעניין לחשוב על ההצעה שלא התקבלה כנגטיב ההצעה של גבע שהתקבלה והוצגה ב 2015 אז נבחר כנציג ישראל באירוע. בעבודה ” ארכאולוגיה של ההווה” צבירה, הכברה ואגרנות החליפה את הריק שהציע ב 2003, והחוץ של ביתן הוסתר וטושטש תחת צמיגים בעבודה דמויות משרבייה (שאסוציאציית השרפה שלהם כפעולת מחאה ריחפה מעליו).

כאמור החלל בחדר הפרויקטים הוא כתת מודע של התערוכה בדירת הרזדינסי .

זו בנויה כמשפט ארוך, ללא הפסקות, זרם תודעה של עבודות, חפצים מצויים, ופרטי אספנות. היא טרופה מבחינה כרונולוגית ובכל זאת בעלת היגיון פנימי, כפקעת זיכרון שהותרה. הצופה הולך במבוך הזיכרון, אמנם ללא חוט אריאדנה אך עם ההיגיון המבני שמכתיבה הדירה – דלתות וחלונות, מסדרון ומרפסות, חלל ציבורי וחלל פרטי. מסכים עליהם מוקרנת שיחה של גבע עם אורחים אודות התערוכה מוצבים בשני חדרים וחבל. השיחה המוסרטת מפריעה למיצב אף שהיא מעניינת בפני עצמה.

השיח בין הדירה, בסגנון הבינלאומי, לעבודות של גבע, הופך את התערוכה למיצב אחד גדול.

הדירה שהיא חלק מבניין הדירות שבנו טוני ומקס ליבלינג שהגיעו לתל אביב ב 1933 בצל עליית הנאציזם בגרמניה ורובו הושכר למשפחות רופאים ממרכז אירופה. כך הבית היפה בסגנון הבינלאומי הוא ביתם של פליטים שמצאו עצמם מוקעים מהתרבות שהשלו עצמם שהם אזרחיה. אמנם פליטים ששמרו על ארשת מכובדות עם רטוריקה של בניית אוטופיה מודרניסטית (את הבניין תיכנן דב כרמי) אך בכל זאת פליטים. העבודות של גבע, עם איזון מסוימת מאד של עידון וחספוס נוגעות במקומות, באסתטיקה שיצר תהליך השימור המיוחד של בית ליבלינג (מרכז מחקר של העיר הלבנה). שימור המבנה לא נועד להחזיר לו מראה חדש – על קירותיו נותרו שכבות צבע ו”לוחות הצבעים” (כתמי צבע בדרך כלל מגוון דומה שמשמשים לבחירת גוון מדויק ), ופריטי הבניין המקוריים בו שופצו ולא הוחלפו בזהים – חדשים. סימן השנים שחלפו ניכר בו היטב.

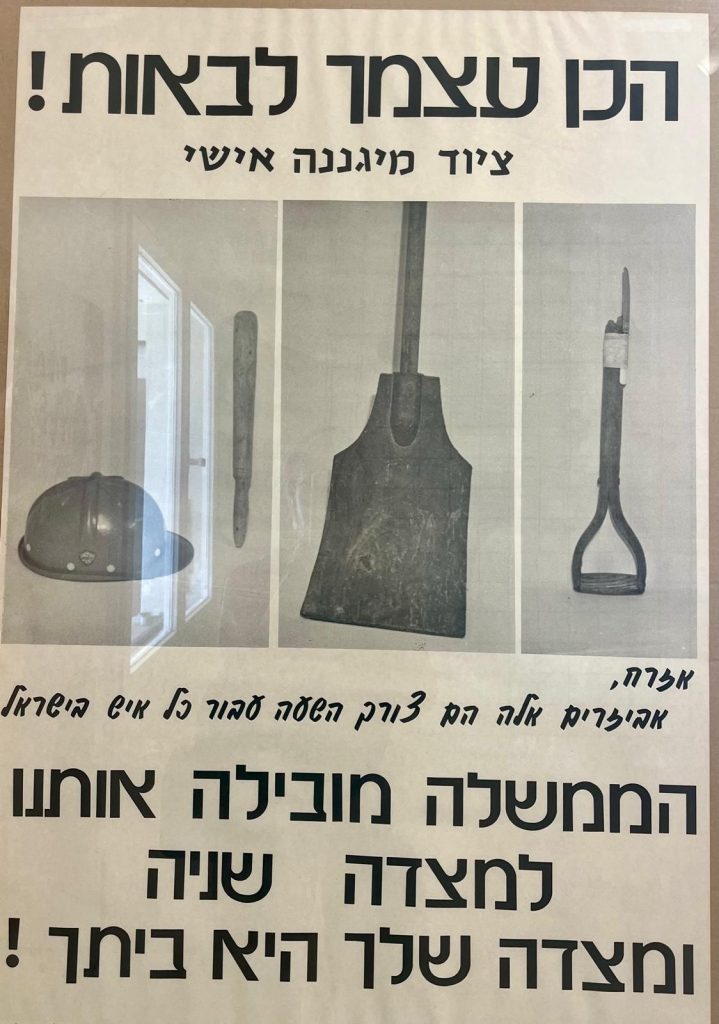

גבע הציב מיטת סוכנות ללא רגלים כפסל רצפה, ומרצפת מצוירת בודדת על מזגן, סורגי מתכת שהפכו מקום איכסון, לצד ציורי כאפיות ומרצפות שומשום (טרצו) הציורים המזוהים איתו וביותר. בשפה ה”ציבי גבעית”, המבוססת על זיכרונות שיעורי מולדת של שנות החמישים, חוזרות ומופיעות בעבודות שונות מפות הארץ בגבולות שלפני הכיבוש ב 1967, חוזרים ומופיעים משולשים כמו לוח שש בש, ושרידי חומרי בנייה כמו שבכת מתכת עליה שאירות בטון. גבע שתל אובייקטים כמו קופסת ופלים (בטעם לימון) עליה מופיע כיפת הסלע וכיתוב בערבית במטבח, או צינור שחור שכמו פסל של ריצרד סרה חותך את החלל וגם מעקר אותו מכל אפשרות לפונקציונליות. גבע מציג סוג מסוים שלArte Povera ARTE ונראה קרוב יותר לתנועה האירופאית הזו, או לפופ האמריקאי של ראושנברג או מאשר למה שזכה לשם “דלות החומר” הישראלית ונראה לרוב כהדהוד חיוור ומתיימר לתנועות אלו (ואחרות).

התערוכה נעשתה כעבודה מצטברת, לאורך מספר שבועות, והשפעתה על הצופה מצטברת אף היא – פרט ועוד פרט, ציור לצד זכוכית מרוחה בצבע שמסגר (ומזכירה עבודות אמנים ישראלים כמו גיטלין או נוישטיין בשנות ה 70 וה 80) שלט מסנדלר ( שמזכיר את הנוסח המתון של דאדא /סוראליזם של אריה ארוך), לוח קרטון מחורר וממוסגר.

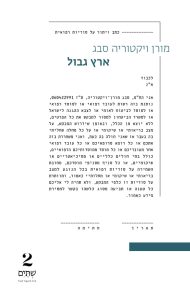

עבודות טעונות כמו משולש שכתוב עליו “סיפורה של אמנות ישראל” ו צילום אביו של גבע, האדריכל יעקב גבר, צופה בעבודות על כיפת מסגד שתיכנן ועבודה העוסקת בתסמונת מצדה הישראלית, שנעשתה כשגבע היה סטודנט, מהוות עוגנים בתערוכה – עבודות שעוצרות את המבט המשוטט.

המפגש בין התקוות ושאיפות הגלומים בקירות המגורדים משכבות צבע והעבודות הפצועות – חשופות של גבע, הופך את “מה שהיה ומה יהיה” למסע פנימה לזיכרון, געגוע ואולי צער משותף של האמן והצופה.

אוצרת: סברינה צגלה

בית ליבלינג אידלסון 29, תל־אביב–יפו א עד ה בשעות 8:00–19:00

שישי 8:00–14:00 שבת 9:00–14:00

Tsibi Geva What Has Been and What Will Become

Tsibi Geva’s What Has Been and What Will Become is an excellent exhibition, one of the best – perhaps his best. It is direct, sincere, with numerous contexts beyond the usual pairing of Geva and Zionist history, or Geva and the kibbutz ethos, or the label of preachy or elegiac applied to the reading of his work of recent years, especially the past year.

The exhibition is essentially two parts installed in two spaces in the Liebling House – a wise curatorial choice by Sabrina Cegla, especially for a veteran artist such as Geva who has such an extensive oeuvre.In the ground floor Projects Room, Geva’s proposal for the Venice Biennale of 2003 – which was not accepted – is exhibited. It is the subconscious underpinning of the major part of the exhibition installed in the residency apartment on the third floor. The overall motif of both parts of the exhibition are circles of destruction and construction, ruin and renewal.In 2003, Geva proposed razing the Israeli pavilion in Venice with a car loaded with explosives to blow up the building in a symbolic suicide of Israeliness. Unavoidable are the thoughts of the historical terror explosions including blowing up of the King David Hotel in 1946 by Etzel, or the first Sidon disaster in which the IDF command HQ in Lebanon was blown up in 1982. Geva proposed to take advantage of the planned renovation of the pavilion to destroy the building in toto, and speak of its rebuilding, referring to mythical contexts such as the Great Flood, among others.

It seems that Geva knew it wouldn’t be accepted while submitting the proposal, especially not during the Second Intifada with its string of suicide bombings. He continued with the conceptual idea of blowing up traditional Modernism, similar to Rauschenberg’s Erased De Kooning Drawing (1953), in which destruction was the creative act. Another well-known example is Ai Weiwei’s Dropping a Han Dynasty Urn (1995), destroying an urn of great symbolic and monetary value.

It is interesting to think about Geva’s 2003 proposal as the negative of his proposal submitted for the 2015 Biennale which was exhibited and which represented Israel. In “Archaeology of the Present” accumulation, magnification, and hoarding replaced the void he proposed in 2003, while the pavilion’s exterior was hidden and blurred under tires in a work that simulated a Middle Eastern mashrabiya partition, the tires with their associations of tires burned in Palestinian protests.

If we consider the Project Room as the subconscious of the exhibition, it may be said to be structured as a long sentence without breaks, a kind of stream of consciousness of artworks, found objects, and collector’s items. It is mixed up chronologically yet bears an inner logic, like an unraveled skein of memories, The visitor walks through the labyrinth of memory, without any Ariadne thread but with the structural logic dictated by the Residency Apartment – doors and windows, a hall and balconies, public and private spaces, screens with a projection of Geva talking with guests about the exhibition in both rooms. This is a pity since the projection disturbs the installation, despite being interesting on its own.

The dialogue between the International Style apartment and Geva’s works transforms the exhibition into one large installation. The apartment is in the apartment house built by Tony and Max Liebling who arrived in Tel Aviv in 1933 with the Nazis’ rise to power in Germany. Most of the apartments were rented out to families of doctors who had immigrated from Eastern Europe. Liebling Haus became the home of refugees who found themselves disinherited from the culture they felt was theirs. Nevertheless, they maintained their respectful expressions with the rhetoric of building a modernist Utopia, even though they were refugees. (The building was designed by Dov Karmi).

Geva’s artworks, with their specific balance of delicacy and crudeness, touch upon places and aesthetics created by the building’s unique conservation process and which turned it into the White City Center for research. The preservation was not designed to restore a new look. On the contrary, it still shows the “trial and error” patches of paint samples on the walls and layers of paint, and original building details were renovated and not replaced by identical new ones. The passage of time is visible.

Geva installed a legless simple bed on the floor of the type that the Jewish Agency gives to new immigrants, as a sculpture. He placed a drawing on a single floor tile over the air conditioner, metal bars that became a storage area along with drawings of keffiyot and terrazzo floor tiles identified with Geva’s art language, based on civics lessons of the 1950s. Images such as those that reappeared in his various works with maps of Israel showing the pre-1967 borders are on triangles similar to backgammon boards, with construction materials such as layers of metal on which remnants of concrete are placed.

Geva placed objects such as a package of lemon-flavored waffle cookies with a picture of the Dome of the Rock on it and an inscription in Arabic in the kitchen, or a black pipe looking like a Richard Serra sculpture cutting through the space and removing all possibilities of functionality. Geva proposes a sort of Arte Povera, looking closer to this European movement or to the American Pop Art of Rauschenberg, showing why he was named as being part of the Israeli “want of matter” art which seems to be a pale version of the aforementioned movements.

The exhibition came together as a cumulative work over several weeks, with the impact of viewers also entering into it – item after item, a painting smeared with paint (reminiscent of works by Israeli artists such as Gitlin or Neustein in the 1970s or ‘80s), a shoemaker’s sign (reminiscent of the Dada/Surrealist works by Arieh Aroch), or a framed cardboard with holes.

Charged works such as a triangle inscribed with the words “The Story of Israeli Art” and a photograph of Geva’s father, Architect Jacob Gever, observing work on the dome of a mosque he designed, and a student work by Geva engaging in the “Masada complex” constitute anchors of the work – works that stop the wandering gaze.

The encounter between the hopes and ambitions embodied in the walls with their scraped paint layers and Geva’s “wounded”/exposed artworks transform Geva’s “What Has Been and What Will Become” into a journey into memory, yearning, and perhaps, sorrow shared by artist and visitor.

Curator: Sabrina Cegla

Liebling Haus – White City Center, Idelson 29, Tel Aviv-Yafo

Sun.-Thurs.8:00-19:00. Fri. 8:00-14:00, Sat. 9:00-14:00