שנת אפס נשארת במחשבות – צרוף של עבודות מצוינות, רגע היסטורי שמהדהד בקיום הישראלי בכאב שלא קהה ותערוכה שעשויה היטב.

העבודות המוצגות, הן ברובן מהיצירות שהביא לארץ ד”ר קרל שוורץ, מנהל מוזיאון תל אביב הראשון לאורך שנות ה 30 מגרמניה הנאצית. עד שהחליט להגר מגרמניה בגיל 48 היה שוורץ, במידה רבה התגלמות אידאל ה Bildung – ההשכלה וההתפתחות הרוחנית מוסרית שטיפחה הקהילה היהודית בגרמניה מהמאה ה 19 ועד לעליית הנאציזם. הבורגנות היהודית, לתוכה נולד, ראתה בכך את המפתח להתערות שוויונית והפכה למקדמת נלהבת של האומניות ואוונגרד תרבותי, לצד שימור מסוים של יהדות בעיקר כתרבות. שוורץ למד תולדות האמנות אצל גדולי ההוגים של ראשית המאה, אצר אמנות, כתב והקים הוצאה לאור. בין היתר כתב בכתב העת “Ost und West” שעסק בתרבות עכשווית של יהודי מזרח אירופה ומערב אירופה במטרה לגשר ביניהם. הקמת מוזיאון הקהילה היהודית בברלין, בראשו עמד הייתה אמורה להיות פרויקט חייו. המוזיאון נפתח שבוע בדיוק לפני העלייה של היטלר לשלטון, בצל הרוחות הרעות שנשבו אך לפני שמידיות וגודל הסכנה התבררה.

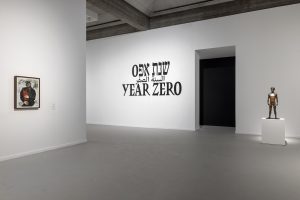

שנת אפס אינה שחזור המוזיאון היהודי אך היא מצליחה ללכוד משהו מהתחושה של שיקול דעת אמנותי, משהו מרוח ה Bildung על מלוא רוחב היריעה, מפגש מעניין של שמרנות עם מידה של פתיחות. בכניסה הדרמטית לחלל, על רקע שם התערוכה בגדול בשחור על לבן ניצב פסל דוד הנער, של ארנולד צדיקוב, מוצבת מול “יהודי עם ספר תורה” של שאגל. דוד של צדיקוב דמות בהתאם לאידאלים של גבריות בנות התקופה (וזיכרון פיסול רנסנסי), היפוך לסטראוטיפים אנטישמיים וציורו של שאגאל מ 1929, שנים אחרי שעזב את רוסיה, הוא התרפקות על היהודי המסורתי המזרח אירופאי, זה שאמור היה להשתחרר על ידי המהפכה הקומוניסטית, אך כמו המשטרים האוטוריטריים שקדמו לה דרסה אותו. מיד לאחר הכניסה מתגלה יהודים מתפללים בבית הכנסת ביום הכיפורים, של מאוריצי גוטליב, 1878 במלוא הדרה, ובתלייה נמוכה במיוחד, כזו המקרבת לדמויות קירבה אינטימית ממש.

שוורץ עזב את גרמניה חודשים ספורים אחרי עליית הנאצים והפך למנהל המוזיאון שרק נפתח בתל אביב. בזכות מעמדו האיתן בעולם התרבות האירופאי שכנע אספני האמנות יהודים לתרום ולהשאיל עבודות נפלאות למוזיאון. למרות דגש על עבודות אמנים יהודים, להם נשקפה סכנה מיוחדת, הרי גם עבודות אמנים לא יהודיים, כאלו שלא השתייכו לקאנון מועדף רשמית על ידי הנאצים הגיעו לארץ (בפועל היו נאצים רבים שבזזו לאוספיהם הפרטים אמנות מודרנית מצוינת). כמה וכמה מהאמנים שעבודותיהם בשנת אפס הוצגו בתערוכה הידועה לשמצה אמנות מנוונת ב 1937, בהם גם וילי יקל שעבודותו “ערפדית” מ 1910 בולטת בתערוכה .

בתערוכה גם עבודות של אמנים שהתקבלו אחרי שנותיו של שוורץ במוזיאון אך שייכות ברוחן לאותו עולם יהודי-גרמני פרוגרסיבי ופתוח, עולם שהאמין בכל ליבו בזוהר הרגע ההיסטורי של רפובליקת ויימאר קצרת הימים.

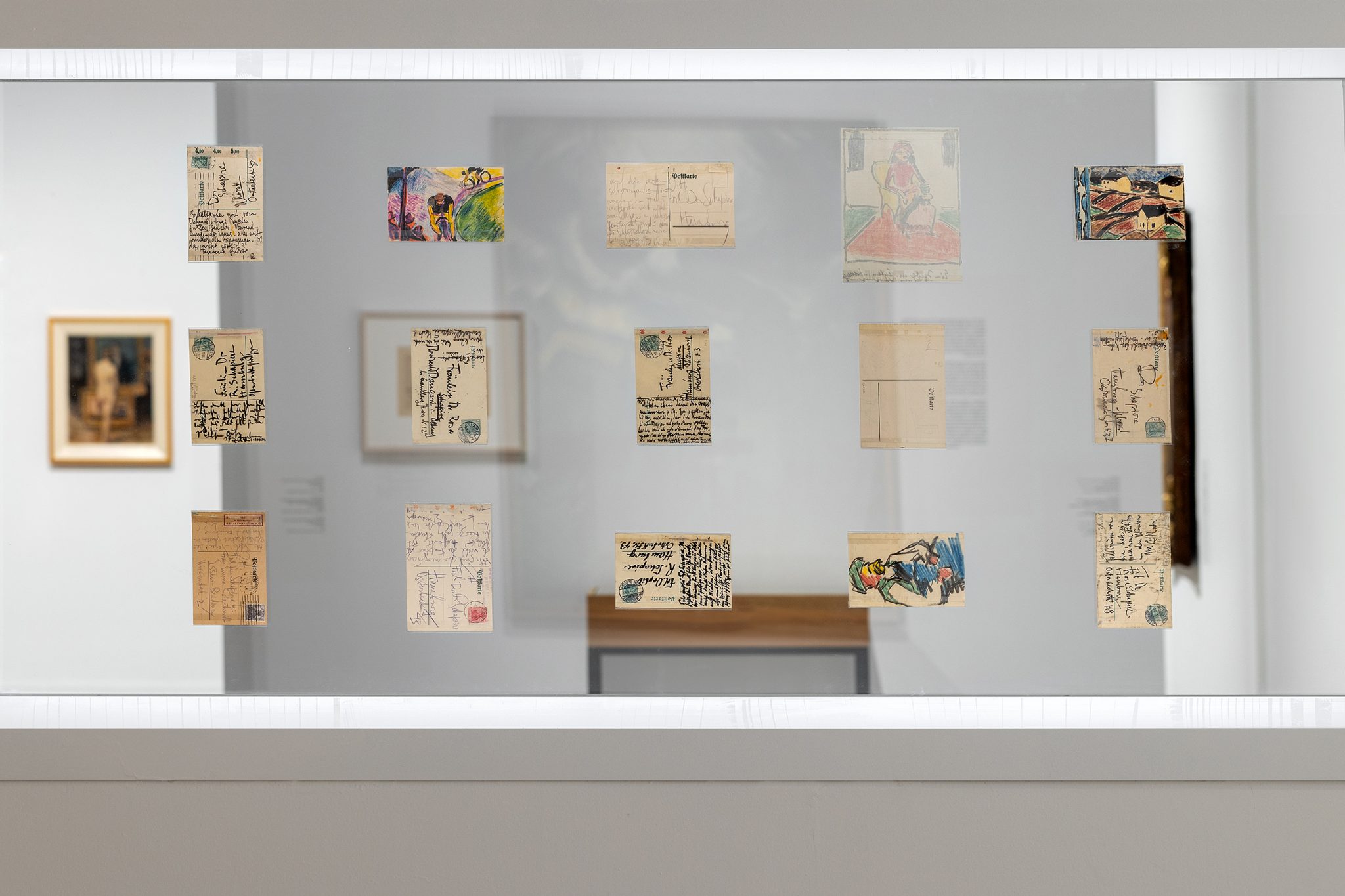

האצירה של נעה רוזנברג אינטליגנטית ואלגנטית והמעברים וחלקיה השונים של התערוכה הגדולה מאירים ונמצאים בדיאלוג זה עם זה. היא גם מצליחה, דרך הצגת עבודות שלא הוצגו לצד כאלו שתולות כבר שנים באולמות האוסף הקבוע, לתת קריאה רחבה לאמנים כמו אורי לסר ( שדומה שהגיע הזמן להציגו בתערוכת יחיד). פרק יפה הוא של האמנים האקספרסיוניסטים מקבוצת הגשר בוויטרינת זכוכית שקופה משני צדייה מוצגות גלויות מצוירות ששלחו אמנים מקבוצת הגשר לד”ר רוזה שפירה, חוקרת תולדות אמנות שעקבה וליוותה את עבודת הקבוצה ונמלטה מגרמניה לאנגליה. העבודות הקטנות והאינטנסיביות הללו מרתקות, בבחינת תמצות של תנועות גדולות יותר לשטח דף קטן. בסמוך מוצגות עבודות מצוינות של מקס פכשטיין, חבר קבוצת הגשר (שנשאר בגרמניה והביע תקופה מסוימת אהדה למשטר הנאצי אף שהוקע על ידי). בולטות במיוחד אלו שיש בהן אובייקטים שהביא ממסעותיו באוקיאנוס השקט. המבחר בתל אביב אינו נופל באיכותו מהמבחר של עבודותיו במוזיאון “הגשר” בברלין.

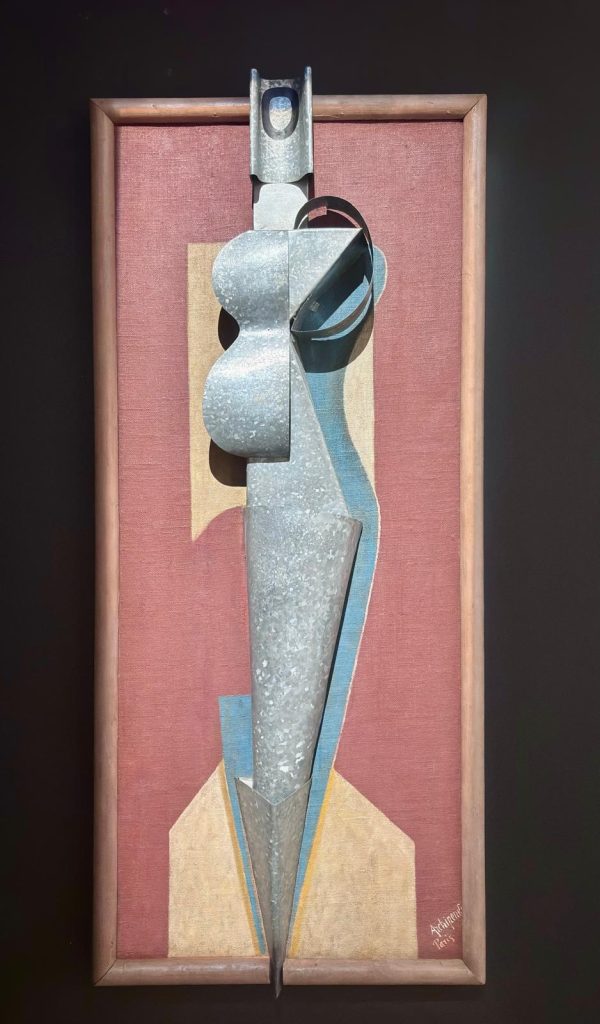

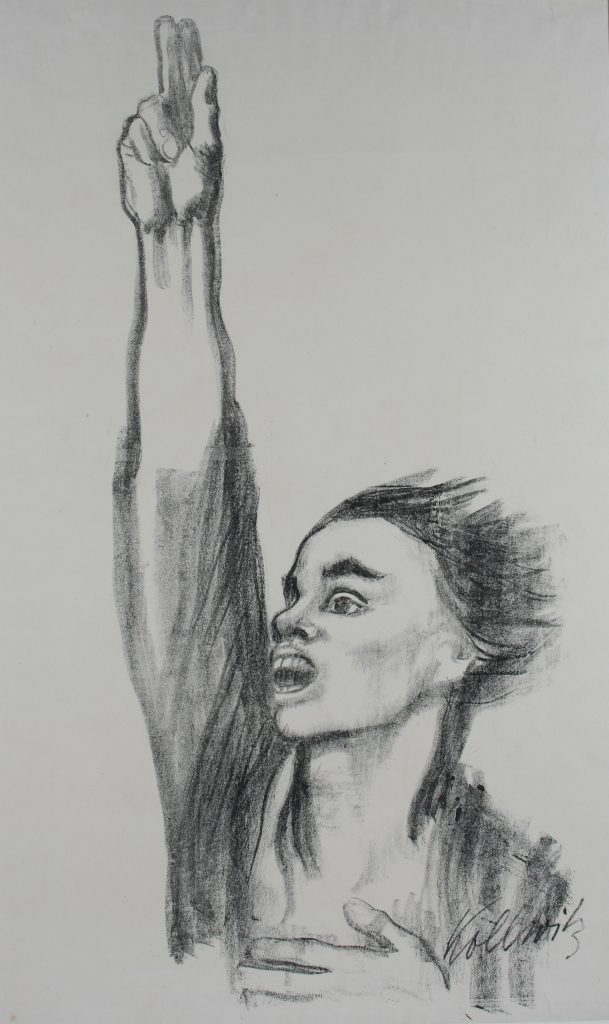

שלושה חללים מובחנים בתערוכה – לאוסף ארכפינקו לעבודות קתה קולביץ וארנסט בארלך ולפרסומי הדפסי האבן ” מלחמה ואמנות” שראו אור לאורך מלחמת העולם הראשונה.

אוסף ארכיפנקו הוצג במוזיאון אך כבר שנים לא נהנה מתשומת לב כבתערוכה הנוכחית. העבודות שהגיעו לארץ החל מ 1933 כוללות את אחת העבודות שהוצגו בביתן הרוסי בביאנלה בוונציה ב 1920, בביתן אותו אירגן הקונסול הרוסי בעיר, שעדיין החזיק בתואר שלוש שנים אחרי המהפכה הקומוניסטית מפני שלאיטליה עדיין לא היו קשרים דיפלומטיים עם המשטר החדש. ברגע אי הבהירות הזו הציגו בביתן טובי האמנים הרוסים הגולים.

קולביץ, אמנית לא יהודייה עמדה לצד חבריה היהודים (ובין היתר הייתה מקומץ האמנים שהגיעו ללווייתו של מקס ליברמן, האמן היהודי הדגול שהיה, עד עליית הנאצים, ראש האקדמיה לאמנות בברלין ונשיא חבר המנהלים של המוזיאון היהודי). היא מוצגת לצד ארנסט בארלך. העבודות של שניהם אקספרסיביות, רוויות אהבה אדם. אחדות מעבודותיה הפכו למזוהות עם תנועות שלום ומחאה משנות ה 20 ועד היום. החלל המוקדש להדפסי האבן שיצאו במהדורות זולות לארוך מלחמת העולם הראשונה עוקב אחרי חוט ההתפכחות מפרץ הלאומנות של ראשית המלחמה להבנת גודל הזוועה בסופה.

ההשוואה בין שנת אפס לבין התערוכה סוף היום: מאה שנים לתנועת האובייקטיביות החדשה מעניינת. הן יכלו להיות תערוכות משלימות – בבחינת תמונה של אוונגרד לעומת תמונת זרם מרכזי של אותן שנים. סוף היום מעוצבת לעילא כולל כורסאות לישיבה, בר, ווילון קטיפה אדום. מתלווה לו סיפור הניתן לצופה כעין מדריך קולי, המתאר יום בחיי אמן מהבית דרך הסטודיו ועד בר בלילה. למרבה האכזבה חלק ניכר מהעבודות בינוניות. למעשה אין בה אף עבודה שהיא אובייקטיביות חדשה במיטבה, אף אחת שמעבירה את הקושי, הארוס, הארסיות והנואשות של העבודות המעולות של תנועה זו. דיוקן אנה גביונטה, 1927 של כריסטיאן שאד, הבולט באמני התנועה, היא מהעבודות היפות בתערוכה אך רחוקה מלהיות שאד במיטבו. האריזה היפה של התערוכה והניסיון להמיר רקע היסטורי במדריך קולי רדוד למדי, אינם מצילים את התערוכה אלא מדגישים את הבינוניות. המוזיאון היהודי בברלין, ש שנת אפס מתייחסת אליו (במישרין או בעקיפין), הוקם כאמור כמוזיאון הקהילה להיסטוריה, יודאיקה ותרבות בדגש התרומה היהודית לתרבות גרמניה. האמנות שהוצגה בו היוותה חלק מהתרבות והמוזיאון לא ניסה למפות אוונגרד של זמנו ולכן מדובר, ברובן, בעבודות שכבר היוו חלק מהזרם המרכזי בשנות ה שלושים. שנת אפס, דורשת צפיה קשובה כשהרקע ההיסטורי הכרחי. היא מצליחה ליצור מפגש אינטנסיבי עם ובין העבודות והזמן בו היא דנה, כשהאלגנטיות בה היא מוצבת אינה מדללת ולו במעט את הדרמה.

אוצרוּת נועה רוזנברג

מוזיאון תל אביב לאמנות

Year Zero

Year Zero lingers in the mind—a convergence of outstanding works, an historical moment that reverberates through Israeli existence with undiminished pain, and an exhibition extremely well done.

Most of the works on view were brought to Palestine-Eretz Israel from Nazi Germany by Dr. Karl Schwarz, the first director of the Tel Aviv Museum, from throughout the 1930s, beginning in 1933. Until his decision to leave Germany at the age of 48, Schwarz was, in many respects, an embodiment of the Bildung ideal—the model of intellectual, moral, and spiritual development fostered by the German-Jewish community from the 19th century until the rise of Nazism. The Jewish bourgeois milieu into which he was born regarded this ideal as the key to equal integration and became an ardent patron of the arts and of the cultural avant-garde, while maintaining a moderated sense of Jewishness, primarily as culture.

Schwarz studied art history under the leading thinkers of the early 20th century, curated exhibitions, wrote extensively, and founded a publishing house. Among other activities, he contributed to the journal Ost und West, devoted to contemporary Jewish culture in both Eastern and Western Europe, with the aim of bridging the two. The establishment of the Jewish Community Museum in Berlin, which he headed, was intended to be his life’s work. The museum opened exactly one week before Hitler’s rise to power, under ominous skies, though before the immediacy and magnitude of the danger were fully grasped.

Year Zero is not a reconstruction of the Jewish Museum, yet it succeeds in capturing something of its curatorial considerations—something of the Bildung spirit in its full breadth: an interesting encounter between conservatism and cautious openness. In the exhibition’s dramatic entrance, against the stark black-on-white title, Arnold Zadikow’s sculpture Young David faces Chagall’s Jew with a Torah Zadikow’s David, aligned with contemporary ideals of masculinity (and the memory of Renaissance sculpture), stands as a reversal of antisemitic stereotypes. Chagall’s painting from 1929, created years after his departure from Russia, is a tender meditation on the traditional Eastern European Jew—the figure meant to be liberated by the Communist revolution, yet crushed by it, as by the authoritarian regimes that preceded it. Immediately beyond the entrance is Maurycy Gottlieb’s Jews Praying in the Synagogue on Yom Kippur (1878), shown in all its splendor and hung unusually low, drawing the viewer into an almost intimate proximity with its figures.

Schwarz left Germany several months after the Nazis came to power and became director of the newly founded museum in Tel Aviv. Thanks to his solid standing in European cultural circles, he persuaded Jewish art collectors to donate and lend remarkable works to the Museum. Although emphasis was placed on Jewish artists, who faced particular danger, works by non-Jewish artists—especially those excluded from the official Nazi canon—also reached Palestine-Eretz Israel (indeed, many Nazis privately looted superb modern art for their own collections). Several of the artists featured in Year Zero had been included in the infamous 1937 exhibition Degenerate Art, including Willy Jaeckel, whose Vampire (1910) stands out in the exhibition.

The exhibition also includes works by artists acquired after Schwarz’s tenure but which, in spirit, belong to the same progressive, open German-Jewish world—a world that believed wholeheartedly in the historical radiance of the short-lived Weimar Republic.

Noa Rosenberg’s curation is intelligent and elegant; the transitions and sections of this expansive exhibition illuminate one another and engage in a productive dialogue. By juxtaposing works long displayed in the permanent collection with others rarely shown, she offers a broader reading of artists such as Lesser Ury(who seems overdue for a solo exhibition). A particularly fine section is devoted to the Expressionists of Die Brücke. In a glass vitrine visible from both sides are illustrated postcards sent by members of the group to Dr. Rosa Schapire, an art historian who closely followed and supported the group and later fled Germany for England. These small, intense works are mesmerizing, condensing expansive movements into the space of a very small area. Nearby are excellent works by Max Pechstein, a member of Die Brücke (who remained in Germany and for a time expressed sympathy for the Nazi regime, despite being ostracized by it). Especially striking are those incorporating objects he brought back from his travels in the Pacific. The selection shown in Tel Aviv rivals in quality that of the Brücke Museum in Berlin.

Three distinct galleries are devoted respectively to the Archipenko collection, to works by Käthe Kollwitz and Ernst Barlach, and to thelithographs War and Art published throughout the First World War.

The Archipenko collection, long part of the museum’s holdings, has not received such focused attention in years. The works brought to the country from 1933 onward include one shown in the Russian Pavilion at the 1920 Venice Biennale—a pavilion organized by the Russian consul, who retained his title three years after the Communist Revolution, as Italy had yet to establish diplomatic relations with the new regime. In this moment of political ambiguity, leading Russian émigré artists were exhibited there.

Kollwitz, a non-Jew, stood firmly alongside her Jewish colleagues and was among the few artists who attended the funeral of Max Liebermann—the eminent Jewish artist who, until the Nazi rise to power, headed the Berlin Academy of Arts and served as president of the board of the Jewish Museum. She is presented here alongside Ernst Barlach. Both artists’ works are deeply expressive and imbued with humanistic compassion. Several of Kollwitz’s images have become identified with peace and protest movements from the 1920s to the present. The gallery devoted to lithographs issued in inexpensive editions during the First World War traces the arc from the early surge of nationalism to the sobering realization of the war’s ultimate horror.

The comparison between Year Zero and the exhibition End of the Day: One Hundred Years of New Objectivity is instructive. They could have functioned as complementary exhibitions—one offering a view of the avant-garde, the other a portrait of the mainstream of the same period. End of the Day is exquisitely designed, complete with armchairs, a bar, and a red velvet curtain. It is accompanied by a narrative almost like an audio guide describing a day in the life of an artist, from home to studio to a nighttime bar. Yet, disappointingly, a substantial portion of the works are mediocre. The exhibition contains not a single work that represents New Objectivity at its best—none that conveys the movement’s tension, eros, bite, and despair. The Portrait of Anna Gabbionta (1927) by Christian Schad, one of the movement’s leading figures, is among the exhibition’s finer works, yet it falls far short of Schad at his peak. The elegant packaging and the attempt to replace historical context with a rather shallow audio narrative do not redeem the exhibition; they only underscore its mediocrity.

The Jewish Museum in Berlin, to which Year Zero refers—directly or indirectly—was established, as noted, as a community museum devoted to history, Judaica, and culture, emphasizing the Jewish contribution to German culture. The art shown there formed part of this broader cultural framework; the museum did not aim to map the avant-garde of its time. Consequently, most of the works belonged to what was already the cultural mainstream of the 1930s.

Year Zero demands attentive viewing, with historical context as an essential component. It succeeds in forging an intense encounter between the works and the time they address, while the elegance of its installation does not diminish the drama by the least.

Curator: Noa Rosenberg

The Tel Aviv Museum of Art